Why Do You Shiver?

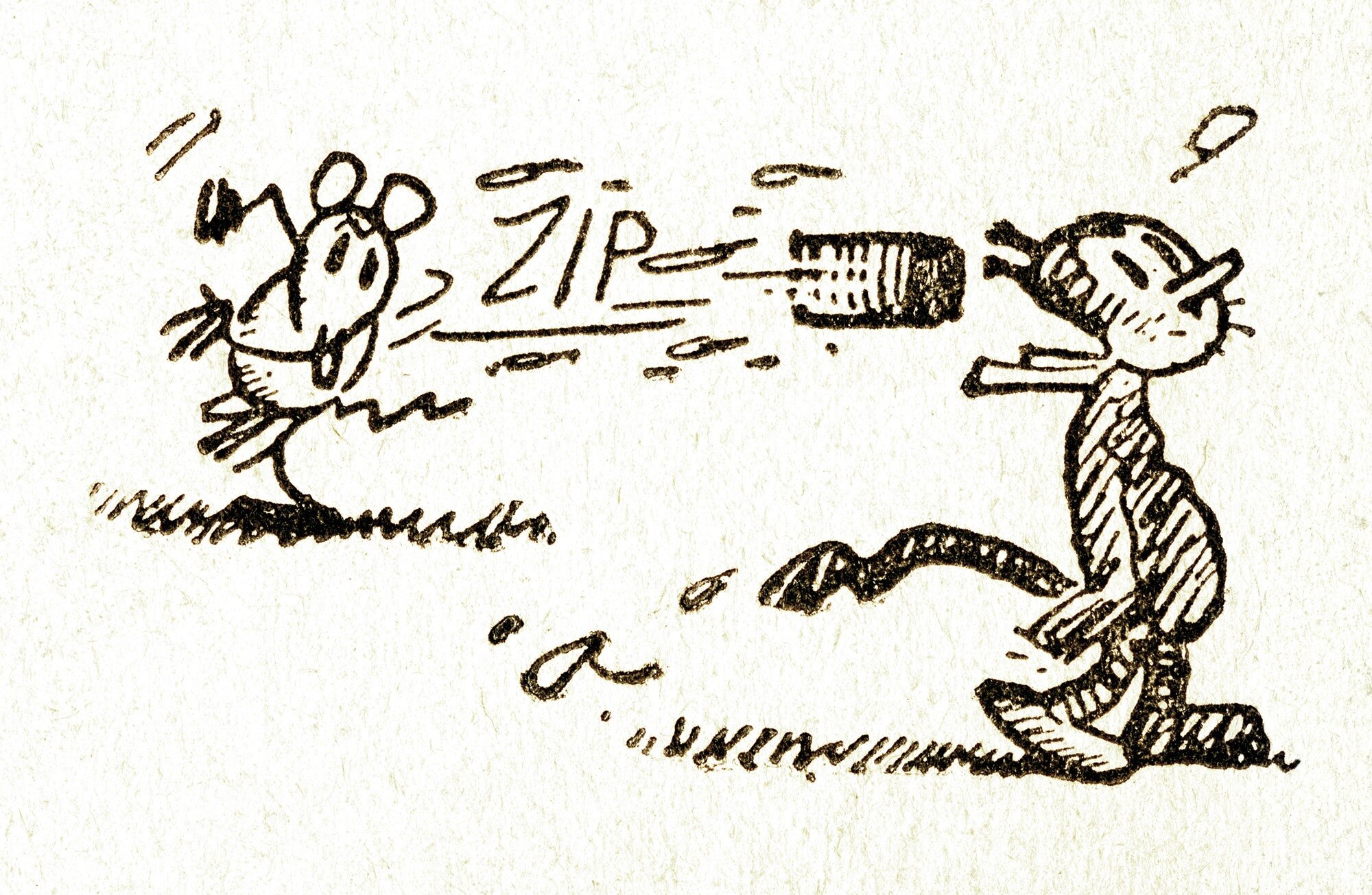

George Herriman’s Krazy Kat and Ignatz Mouse.

While we shelter in place, a few things keep me going: spending more time with my fiancé and daughter, group phone calls with my co-workers, home projects, and looking around at the art on my walls, now with eyes freshly altered, or jolted onto another frequency, by the recent abrupt change in daily reality. One that keeps jumping out at me, or down, from its spot above the doorway to the hall, is a Krazy Kat strip written by George Herriman in 1922 at the end of the second wave of the Spanish Flu epidemic.

The strip opens with a brick-clutching Ignatz Mouse saying simply, “HE COMES,” setting up an anticipatory moment in which we wonder, even if we already suspect, who will appear. I think of this phrase as I sit in my living room, wondering if “HE” could be an “IT,” in the form of a virus, which I am waiting out, or waiting for, with the same sense of a hanging question.

A shaking Krazy arrives in panel two. The background landscape has totally shifted, a hill with a village replacing a house on a mesa, but somehow Kat and mouse seem not to have moved. Ignatz asks, ”WHY DO YOU SHIVER, HAVE GOT THE AGUE?” Ague—an old word for an illness involving a fever and shivers.

Another lurch in the landscape, yet somehow standing still: a new scene, but placed firmly in panel three of the six identically sized rectangles. Krazy answers, “N-N-N0 I-I-I-I JUST GOT A C-C-HILL.”

”BUT IT’S A WARM DAY,” Ignatz replies while setting down his brick. (Surely the virus has Krazy!, I now think.)

“I KNOW IT—,“ replies Krazy in panel four, in yet another different-yet-same setting. (My house is still my house, but the news makes the familiar walls feel strange—they guard me with different purpose, a barrier from germs circulating outside.)

Ignatz, sitting on his brick, with a look of mild concern, asks, “HOW CAN YOU EXPLAIN THIS CHILL, THEN?” (The two characters stand what appears to me much less than the W.H.O.-recommended six feet apart!)

A fluffed-up Krazy answers: “I TELEPHONED THE DRUGSTORE TO SEND ME A LARGE JAR OF ‘COLD CREAM’ FOR A MASSAGE.” (I can’t help but be reminded of the hoards of people in mostly empty grocery stores pushing and shoving for the last bag of flour, pasta, or beans--no wonder Krazy called in his order! …And why a massage, or perhaps, how? Isn’t the virus spread by touch?)

Ignatz, looking annoyed, replies, ”WELL COLD CREAM ISN’T REALLY COLD, FOOL.” The mouse is beginning to uncover something. Krazy Kat’s symptoms might be of another source, his chill possibly psychosomatic. (And how many times in the last two weeks have I felt a twinge of something in my lungs, my bones, or my head, like that poor Kat! Perhaps Krazy, like me, has been reading too many articles and anxiously picturing all the doorknobs, handles, toilet flushes, and hands that have made themselves available to be touched!)

In the sixth and final panel, the still-chilly Kat reveals, “NO, BUT IT’S ‘ICE CREAM’ THEY SENT ME.” Comic silliness restored, a brush with ague averted, Ignatz stands in front of a fire that was nowhere to be seen in previous panels and offers his usual treatment: “HERE’S A NICE HOT TOASTED BRICK FOR YOU.”

In Herriman’s Krazy world, the brick is a perverse symbol of love. But I wonder, having mapped this century-old strip onto our present moment, the way I find myself re-mapping, re-framing, re-seeing many familiar things these days, what it represents in ours. Unlike most Ignatz-and-Krazy scenes, which end with the brick being thrown, completing a reassuring if cruel pattern, here Herriman leaves me to complete this brick’s trajectory in my 2020 imagination. What will happen this time when the brick lands? Will I be struck with a virus, or a cure?

Chris Oliveria

Los Angeles, April 2020